Consciousness

“If we take eternity to mean not endless temporal duration but timelessness,

then eternal life belongs to those who live in the present.”

- Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

Time ceaselessly marches on, and yet it is always and only ever, now. In that, it seems to possess a dual nature — like the endlessly renewing mists of a waterfall that gives rise to a still and unchanging rainbow — time’s essence as change is something that itself never changes. In this, the true nature of both time and its witness remain a mystery and yet, that time is an essential aspect of existence, its reality allows us to pose a question: What might be its role in the production of mind and consciousness?

Irretractable, our intimacy with Time is imminent and incessant, the flux of which underlies every waking moment of our embodied being. Its flow allows us to know reality, and its entangled relation with consciousness generates, in us, a peculiar kind of meta-awareness, a witnessing “I” whose awareness of awareness results in humanity’s crowning achievement—self-consciousness. The gravity of its invention — of being reflexively self-aware— should not go understated as its reality forms the very heart of what it means to be human. Self-awareness allows us to become self-determining beings while enabling us to perceive what may become actual despite lying in the as-of-yet unwritten future.

“Time hath a wallet at his back,” Shakespeare reminds us, “wherein he puts alms for oblivion.” Self-consciousness — by allowing us to ponder the nature of existence and our relation to it — reveals to us our ever-approaching annihilation. Still, more than that, the freedom inherent in our mind’s agency enables us to determine our identities, to construct and adhere to social ideals and norms, and feel empathy toward others. And although we are still unsure of what time and consciousness genuinely are, this profound mystery we live need not daunt us. After all, we are the most complex creatures in existence (that we know of) and by lifting reality’s veil in the appropriate places can come to know many things.

So, let us begin with time and consider a simple question: What is it? Is it motion, as Aristotle thought? A psychological attitude we project toward past and future as Saint Augustine believed? Or is it a mind-dependent construct, a form of our intuition and gear in our cognitive apparatus, as Kant famously argued? Or maybe, time is a “dimension of our being,” or “the substance of which we are made.” These thinkers, each in their own way, express a truth about time while also evading a concrete definition. Paradoxically, although it’s hard to say exactly what time is, we nevertheless know it very well.

That is to say, we know immediately, through direct intuition and instinct, precisely what time is. Yet despite this intimacy, we find it difficult to put into words the very ‘what’ of it. It is the same with that nebulous term 'consciousness,' both are not "things" in the common sense of that term and are "substances" whose essences cannot be captured by words. A modality of awareness itself, the character of time is not something we can explain, teach, or show to others, but it can be known certainly, by living it. It takes time to know time, and its endless march underlies all our conscious states. As a necessary condition for sentience, time is known best through silence. If one were to mute every sense, say, by entering the tranquil darkness of an isolation tank, they would still daydream and accumulate memory. But suppose one could initiate the cessation of hypnagogic imagery, of visual perception, and the faculty of thought more generally. In that case, one might enter into the unchanging purity of the timeless and eternal present, achieve the penultimate state of spiritual consciousness — known in the East as Satcitananda — and come to know themselves, the very core of their being, as being-consciousness-bliss.

Non-ordinary states of consciousness aside, the “now” is always-already this eternal moment and serves as a temporal window through which we come to know change, persistence, and succession, and arrive at an awareness of awareness itself. For it is only by time’s passage and its coupling to our vivid sense of thought that we become self-conscious — aware of being aware — and achieve that unique, meta-cognitive state. Our mind’s generation of its own inverted eye — the eye we call “I” — is a novel function and technology in the realm of conscious beings. The achievement and invention of self-consciousness is what grants us, language-equipped primates, the capacity to create such an impressively detailed and complex social reality.

But how exactly does our mind generate its own inverted eye? It accomplishes this by superposing knowing in two opposing temporal directions while retaining a self-directed awareness through the ever-rolling present; a singular awareness that contains the just-past, what-is-actual-now, and possibility’s phantom as the just-about-to-happen. Our conscious experience is a sliver of sentience spread over this short temporal window we call “now.” It also reveals self-consciousness as not simply an awareness of awareness, but — as a temporally extended kind of phenomenon — as a somewhat that includes the simple and bare fact that we experience anything at all.

“The original paragon and prototype of all conceived times is the specious present,

the short duration of which we are immediately and incessantly sensible.”

— William James

I | The Temporal Width of Witnessing

No matter what and always-already, we experience consciousness as a kind of flow, an incessant movement that is itself extended in time and possesses a degree of temporal width. Your awareness of this moment is not confined to an infinitesimal “now” but extends bidirectionally from this living-present, reaching into the about-to-happen while simultaneously retaining a degree of the just-past. To better understand these seemingly strange assertions we need to consult the branch of philosophy that deals with the invariant structures of our immediately lived experience; phenomenology and its study of time-consciousness.

Before we continue, a quick distinction: I use awareness and consciousness synonymously, and by them, I mean the bare fact of being aware; it matters not of what. It could be a singular quale isolated within a single sense or the totality of one’s experience including their emotional and physical state. Consciousness itself is a highly curious entity in that any attempt to define it already presupposes its existence. By self-consciousness, I am referring to a kind of meta-consciousness, of being aware of being aware.

Phenomenology comprises a critical investigation into the nature of the world and our embodied being. It analyzes how phenomena present themselves to conscious agents and seeks to understand the invariant structures that underlie their presentation and how it is that we are in touch with the world. As its name suggests, phenomenology is the study of phenomena, but more than a mere logy, (the suffix -logy is a morpheme added to the end of a word to indicate that it is ‘the study of’ the word it is affixed to) it is a method of philosophical inquiry.

As a method, phenomenology asks that we dispense the ‘natural attitude,’ the run-of-the-mill, mundane, and everyday mindset that we habitually and unconsciously carry with us. Instead, it asks that we return our attention to that which is imminent and immediate. For it is only in the here and now that one can analyze the structures of consciousness. But first, allow me to expand on what is meant by the ‘natural attitude.’ We often go about our days in a kind of “captivation-in-an-acceptedness,” an ordinary and mundane state of mind that remains oblivious to the wonderment that is existence itself and finds it totally uninteresting. We take for granted our culture and humanity, that we are rational, domesticated primates who invent laws and corporations and play at economics with fiat, now digital, currencies. We rarely pause to wonder how this is possible, let alone entertain the fact that it is astounding. In learning and knowing so much, complexity becomes second nature, and we can go about our days with minimal distraction and operate efficiently. Seen in this light, the natural attitude may be an evolutionarily inherited psychological strategy and technology that we use to navigate an ever-complexifying environment. Regardless of its existential merit, phenomenology asks that we dispense with the natural attitude, return to a state of curiosity, cultivate an interest in the habitually mundane and return to the here and now. The method even has a name; the epoché refers to a reductive, psychological maneuver that allows us to dispense with all that we take for granted and instead focus solely on what is given to us in the present. To rekindle the wonderment of being by focusing upon this moment only, wholeheartedly and truthfully, and to see it as our only window into the nature of existence.

The ancient Greek origin of the word epoché means “cessation” and “withholding judgment.” It is used in the phenomenological tradition to denote the internal, mental operation of “bracketing” or withholding one’s usually naturalistic assumptions and beliefs. Initially, the ancient Greeks were said to perform the epoché to reach a liberated mental state called ataraxia — an equanimous mode of inner tranquility. Focusing only on what is present in the here and now frees oneself from fear and anxiety. In giving up the concepts, the mental phantoms of the what-was or the could-be outside of this moment, we find that it is without issue and pure and serene. As Twain so eloquently remarked, “I’ve had a lot of worries in my life, most of which never happened.” The epoché can also be considered a tool that aids in the cessation of the engine of thought. A tool meant to reveal the purity of consciousness. Then, it is only in this sphere of being-present-in-immanence that we can begin to analyze the structure of our minds and its relation to time.

One of the first things we realize when we enter this sphere of experience is that it is intentional and that all conscious states have content and are about something. The “what” of these states need not be external to us in the form of physical objects but can also be internal to our being, such as feeling the pangs of hunger or the optimistic hopefulness of an uncertain future. All our embodied being consists of focused, intentional acts like perceiving, anticipating, remembering, imagining, feeling, willing, and judging. We perceive something, anticipate something, and remember something and see that our bearing witness is almost always co-related to that which it is not. In every experience, there is a knower and a thing known, a subject and an object, an individual embedded in an environment.

As the phenomenologist understands it, intentionality asserts that our awareness is never empty and has a focal point. The word ‘intentionality’ comes from the Latin 'intendere,' whose roots mean drawing a bow and aiming at a target. Despite the unfathomable contents of any experience, the crosshair of our intentional directedness picks out just one overarching scheme and homes in on a single aspect or part of our experience. A perception or sensation that can either be chosen at will, like an external object or internal feeling. Or, sometimes, what we concern ourselves with will be selected for us. Events in our environment or subjectivity can arise such that they cannot be ignored and will take center stage of our bearing witness, such as when sadness or anger washes over and engulfs us.

Listening is a passive sense, but to see the focus of one’s willfully directed intentionality, consider the experience of being in a busy restaurant and the audible buzz of countless conversations. We can deliberately attend to whatever we like. Without involving any other senses, we can disengage from listening to our date’s small talk and instead focus on a conversation at another table. And in directing our focus — by aiming our intentionality — what was once inaudible becomes audible. What we attend to becomes real for us, and what we can intend to is not limited to sound, but any sense modality we possess, including our thoughts.

The negative consequence of the aperture of intentionality’s focal lens entails that we miss out on far more than we can ever attend to. But this need not be seen as a complete loss, for it implies that our consciousness is automatically open-ended and inviting. On one side, awareness is endlessly and uncompromisingly a receiver of information, an insatiable well of experience soaking up its environment. Still, on another, we will what we want and attend to what we deem meaningful. We aren’t merely passive receivers of information but are synthesizing and creative agents.

Finally, and to return to time, given that phenomenology analyzes the invariant structures of our awareness, it is no wonder that it has come to study it. Time is arguably the most fundamental and basic element of our lived experience. So, what have they to show for their efforts? In contemplating time as time itself, phenomenologists have demonstrated that our awareness of this very moment is not a sliver in time succeeding others but is a specious, living-present that possesses temporal width. Time, as we experience it directly, is an extended duration underscored by constant dynamism. Our experience is a flowing ‘duration block’ extending beyond the primal present into both the past and future. It is not a succession of instantaneous moments compiling upon one another. The pragmatic philosopher William James was the first to articulate our consciousness’ temporal resolution:

“The practically cognized present is no knife-edge, but a saddle-back, with a certain breadth of its own on which we sit perched, and from which we look in two directions into time. The unit of composition of our perception of time is a duration, with a bow and a stern, as it were – a rearward – and a forward-looking end. It is only as parts of this duration-block that the relation of succession of one end to the other is perceived. We do not first feel one end and then feel the other after it, and from the perception of the succession infer an interval of time between, but we seem to feel the interval of time as a whole, with its two ends embedded in it.”

With this observation, James brought to light that our sentience is itself always-already extended in time and possesses a degree of time-like resolution. A width that would later come to be called specious. The present moment understood in this temporally extended way forms this “paragon and prototype” underlying all sensible experience and will lead us to a conception of time-consciousness as a standing-streaming – a place where we find something timeless embedded in the structure of time itself.

But before we reach that insight, we need to focus the lens of our philosophical scrutiny on peeling back the structured layers of this “duration block” of time. Edmund Husserl was the first to do so, the original phenomenologist whose analysis revealed the tripartite form of time-consciousness. Building on James’ ideas, Husserl would come to show that time-consciousness attends not only to the temporal aspects and modes of objects that exist apart from us but also to the time-like modality of consciousness itself. For Husserl, an “object” is temporal if it has unity across succession and has distinguishable though inseparable parts, such as a melody or the meaning of a sentence. Husserl’s project examines, without eliminating their time-extended coherency, how we synthesize an object of this sort. But one of his most striking results is that time and consciousness are inseparable.

“The pure present is an ungraspable advance of the past devouring the future.

In truth, all sensation is already memory.”

― Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory

II | The Genesis of Self-Awareness and Threefold Structure of Time-Consciousness

Taking this specious living-present as self-evident and subjecting it to further analyses, Husserl realized that consciousness not only attends to what is imminent now but preserves in it what has determinately come to pass and anticipates what may (given the environment and historical context) come. In seeing this, Husserl distinguishes between three inseparable modalities and shows that time-consciousness has a tripartite structure consisting of what he calls primal impression, protention, and retention.

Consider the everyday experience of listening to the melody in a piece of music, given the key of the song we expect, whether aware of it or not, a specific sequence of notes to sound. Even if we know not what they will be, notes that don’t belong to the song’s key will be experienced as jarring, and although this can be surprising, this doesn’t negate the fact that we anticipate a coherent evolution to the music. Husserl calls this anticipatory, ‘forward-looking’ part of the specious present “protention.” The music’s notes rise; they protend from an undefined and open horizon to become imminent and actual, what Husserl calls “primal impressions.” But no sooner than a primal impression comes into being, does it slips into the past. This just-past phase of time-consciousness is called retention. ‘Awareness’ extends over all three, but only retentions are retained.

We are never without this threefold structure. To recapitulate, we protend the notes of the melody as they rise into our experience from an open and undefined yet environmentally limited horizon. Here they become specific and determinate primal impressions that ceaselessly flow into being retented. It is through this threefold structure that temporal objects are unified and can be known.

Let’s dive into this a little more. Primal impression refers to what is actual now; it is what is imminent, but lacking reference to past and future lacks intelligibility. For a primal impression to be sensible, that is, to make sense, it must be couched between the just-about-to-happen and the just-past — between protention and retention. Due to the continuous flow of consciousness, no sooner than a primal impression comes into being it slips into the past, becoming a retention, a no-longer-actually-present somewhat. Although no longer primal, what is held in retention remains present in our consciousness, experienced in what is now primal but as past. The just-past content held in retention slowly fades as it is filled with more primal impressions, with more musical notes. In the other direction, we experience a protention, a kind of anticipatory openness to the immediate future. Our visual perception supplies us with the notion that we exist in a field of virtual action. The environment reveals itself to us as a sphere of possible activity, through protention we are aware now of what can come to be. We perceive immanent possibility, what is possible for us, and operate and initiate movement based on what we protend.

In any given experience or situation, we have an idea of what to expect. Although the futural direction of our awareness is indeterminate and undecided, we can be surprised, say if the music stops altogether. However, even if we are surprised, the new moment will cohere with what was possible a moment before and the environment remains stable.

Protention and retention form parts of our awareness and reach out from this primal present. Not only are their contents and functions different, but the ‘just-past’ and the ‘about-to-happen’ phases of consciousness have different ontological statuses. What we hold in retention is filled and determinate. At the same time, what we anticipate through protention is unfulfilled and indeterminate but arises from a future of coherent possibility given the context and environment.

To more clearly see the threefold structure of time-consciousness, consider how you comprehend what you’re reading at this very moment. Your awareness itself stretches back, however dimly, to the deliberate choice to read this article, and the meanings of its various parts and paragraphs are retended in you at this very moment. You don’t “remember” that instant but live it now as part and parcel of this one. But more importantly and more vividly, you retend the most-recently-past as it occupies an exalted position in your awareness. The words I have said, and their order are somehow present in this primal impression, with the most recent having the most weight. This is how understanding transpires along temporal lines. Due to the ceaseless unceasing of time-consciousness, primal impressions endlessly turn into and fill what is held and eventually lost in retention. Not only do you retain previous experience in this moment and the primal impression itself, but you also protend expectation that I’m going to finish this sentence and that there will be more to read as your peripheral vision doesn’t tell you of the articles end.

I should point out that retention is not remembering or memory as their difference goes far beyond mere temporal distance. Memory differs in that an event is voluntarily called to mind and re-presented at this moment but as past, as absent. In contrast, retention is automatic, involuntarily, and works to suture together the relevant phases of consciousness and complete the temporal object. Retention remains present to awareness. Memory, naively considered, does not allow us, nor even help us, perceive a temporal object. These few beginning words of this sentence are not remembered by you but present to your sentience now and are perceived as they were when they were primal impressions. A similar situation is true of protention; given our personally lived histories and the degree to which we understand the world, we can imagine and anticipate possible futures by re-presenting mental images of what may come to pass. But imagining futures is not protention.

Finally, Husserl then makes a final distinction between horizontal and transverse intentionality. Why he calls them these will become clear in a moment. Horizontal intentionality is our awareness of time as time itself as we flow along with it and supplies us with our direct intuition and immediate knowledge of it. This type of intentionality holds our previous awareness of time’s flow as flow itself and is present now and is the movement that allows us to come into self-consciousness. We retend not only primal impressions and their contents but also the just-past phase of our very consciousness. Therefore, there are two “objects” held in a retention, the retention itself and an awareness of the retention. Again, it is only by awareness recognizing itself in a strange, acausal feedback loop, that we arrive at the meta-state of self-consciousness.

Husserl refers to the invariant flow of horizontal intentionality as a “non-temporal temporalizing” and claims that it serves as the condition of possibility for knowing anything whatsoever. It is non-temporal because it never changes; it is always and only ever this way. Time and time-consciousness are static and unchanging in this structure, but only through and by it does dynamism enter the world such that the shape of movement is itself the cause and consequence of the temporalization of time. An odd phrase, “non-temporal temporalization” captures the dual nature of time. These thoughts grant weight to the ancient insights of both Parmenides and Heraclitus — whose understandings of time were seemingly at odds with one another. Parmenides, an eternalist, wrote of time and change that they were illusions, unreal and that all times existed always and forever. While Heraclitus, a presentist, wrote that the only real thing was change itself and the window through which we experience it: the present. Through this analysis of time-consciousness, we can see that there exist aspects of our being, and of the universe more generally, that is both timeless and temporal.

Perpendicular to the movement of horizontal intentionality lies transverse. It forms our standard mode of being in touch with all the possible objects of our experience, whether internal or external. Whereas horizontal intentionality indicates our movement lockstep with the arrow of time, transverse intentionality indicates the relation between us and the things — whether percepts or concepts — we experience as other. The “directionality” of transverse intentionality is then “perpendicular” to that of the arrow of time. It moves, like a two-way street, from object to subject and is indicative of our awareness’ connection to the temporal objects we intend. Of course, transverse intentionality moves along with time, but the direction of its attention moves from knower to thing known.

We commonly think of ourselves as subjects in touch with objects that relate in some manner. But when we lose ourselves free and creative activity, this distinction can blur, resulting in a “flow” state that is not too dissimilar to ataraxia. There are levels to this, the pinnacle of which will be considered in the next section. But concerning our self-understanding and self-consciousness, this “transverse” intentional mode fails because we cannot relate to ourselves in that way as we do not stand outside of ourselves and experience ourselves as other. Only horizontal intentionally and the structure of time-consciousness allows for the genesis of self-consciousness and provides a mechanism by which we can relate to ourselves non-paradoxically.

“Time isn’t precious at all because it is an illusion. What you perceive as precious is not time but the one point that is out of time: the Now. That is precious indeed. The more you are focused on [psychological] time—past and future—the more you miss the Now,

the most precious thing there is.” — Eckhart Tolle

III | The Power of Now

This moment, which is always now, is the absolute point of orientation for all conscious experience, for all sentient knowing. Although the contents that stream through our consciousness are endlessly ever-changing, the tripartite structure of time-consciousness and the bare fact of being aware never does, always remaining pure, still, and absolute. This structure, standing outside of time, is non-temporal and serves as the basis for consciousness.

Consciousness, in its true nature, also stands outside of time; what we are aware of always changes but the awareness underlying it is only ever and always “awareness.” Consciousness, as always-the-same and pure as consciousness itself, allows for endless change and in this way is absolute. No other consciousness is required for its self-apprehension. The timeless nature of consciousness is found when we achieve the state of ataraxia and come to find an eternal stillness at the heart of incessant movement. Where we find something timeless hidden in the structure of time itself. The result is a kind of yoga, where our consciousness no longer makes the distinction between what is Home and what is Other, and we arrive at a union with all-that-is. Wherein, an enantiodromedal transformation takes place and “the self as bare point becomes an unlimited Space whose nature is Light or Consciousness. Divinity fuses with the self, thereby becoming the Self, which is at once both God and I.” In this Liberated state of absolute Realization, one comes to know themselves as not only intertwined with the contents of their consciousness but are the contents themselves, the whole thing. The individual mind reveals itself as an interconnected part of an open-ended whole that proliferates unto infinity.

To reframe the pessimistic philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer’s striking image of a rainbow over the waterfall with consciousness, the borrowed metaphor we began with, he would write “The [contents of consciousness] are like the innumerable violently agitated drops of the waterfall, constantly changing and never for a moment at rest; [while] the [structure of time-consciousness and awareness itself] is like the rainbow silently resting on this raging torrent.”

When we discover that we are not the raging torrent of the waterfall but are instead the beauty that is the stillness and illuminating color that is the rainbow, we come to know ourselves as equal and inseparable, even identical in a way as each of us forms a dynamic shape of an oceanic — and undifferentiated in its purity — sea of consciousness. All part of this timeless eye that witnesses itself coming into being. Our material bodies belong to and are expressions of an efflorescent cosmic unfolding that is caught in time, but our true nature, that which connects us all and is lying underneath, is the exact, one and the same “thing” looking out from all of us. In seeing this we become like the sage who “in experiencing the unity of life sees their own Self in all beings, and all beings in their own Self, and looks on everything with an impartial eye.”

Casey Mitchell is an avid reader and incurable thinker who finally thought to pick up the pen to share his thoughts on life and love and the meaning of existence. A lover of philosophy, he is consistently perplexed and amazed by the ever-unfolding universe. He is the creative pulse behind SophiasIchor.com and writes to share his curiosity concerning this mystery we live. Consider purchasing his self-published book The Baseless Fabric of this Vision.

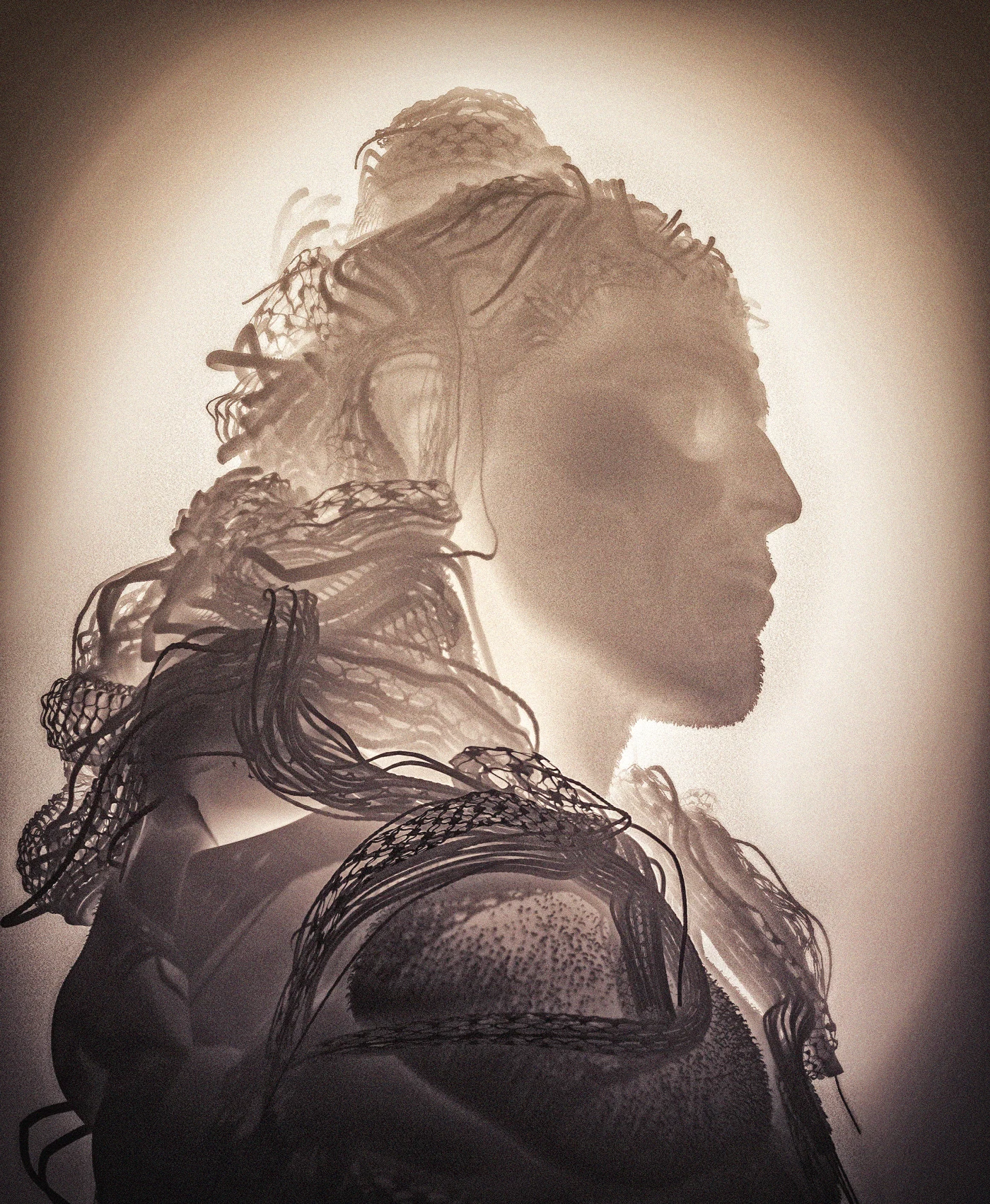

All images in this article are by the insanely talented Android Jones.

This article (The Eternal Efflorescence of Time) was originally created and published by Sophias Ichor and is published here under a Creative Commons license with attribution to Casey Mitchell and sophiasichor.com It may be re-posted freely with proper attribution, author bio, and this copyright statement.